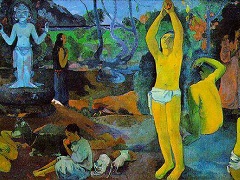

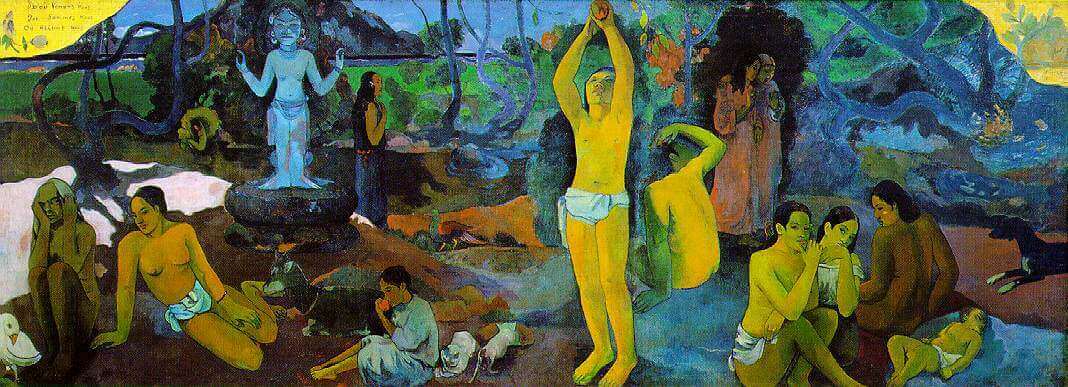

Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Wher Are We Going? 1897 by Paul Gauguin

In December, 1897, Gauguin decided to kill himself. He was sick and miserable, without enough money for medical treatment, he was in debt and abandoned by those who owed him money. His tropical paradise had failed. He wished, before dying, to paint one great, last testamentary picture, and summoning all his strength in a single burst of energy he painted this canvas his largest. The attempt at suicide failed, apparently through an overdose of the arsenic he took, and so in later letters, we have his own comments upon the picture and its genesis:

It is a canvas about five feet by twelve. The two upper corners are chrome yellow, with an inscription on the left, and my name on the right, like a fresco on a golden wall with its corners damaged.

To the right, below, a sleeping baby and three seated women. Two figures dressed in purple confide their thoughts to each other. An enormous crouching figure which intentionally violates the perspective, raises its arm in the air and looks in astonishment at these two people who dare to think of their destiny. A figure in the center is picking fruit. Two cats near a child. A white goat. An idol, both arms mysteriously and rhythmically raised, seems to indicate the Beyond. A crouching girl seems to listen to the idol. Lastly, an old woman approaching death appears reconciled and resigned to her thoughts. She completes the story. At her feet a strange white bird, holding a lizard in its claw [sic], represents a futility of words.

"The setting is the bank of a stream in the woods. In the background the ocean, and beyond the mountains of a neighboring island. In spite of changes of tone, the landscape is blue and Veronese green from one end to the other. The naked figures stand out against it in bold orange.

"If anyone said to the students competing for the Rome Prize at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, the picture you must paint is to represent Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? what would they do? I have finished a philosophical work on this theme, comparable to the Gospels. I think it is good."

Gauguin did more than describe the allegorical subject of this picture. He also told of the method and manner of its execution, stressing what his predecessors in romanticism would have called inspiration, and his twentieth-century heirs the uncontrollable workings of the subconscious, true source of the artist's genius:

I worked day and night that whole month in an incredible fever. Lord knows it is not done like a Puvis de Chavannes: sketch after nature, preparatory cartoon, etc. It is all done from imagination, straight from the brush, on sackcloth full of knots and wrinkles, so the appearance is terribly rough.

"They will say it is careless, unfinished. It is true that one is not a good judge of one's own work, nevertheless I believe that this canvas not only surpasses all my previous work, but that I will never do anything better or even like it. Before dying I put into it all my energy, a passion so painful, in terrible circumstances, and a vision so clear, needing no correction, that the hastiness disappears and life surges up. It doesn't smell of the model, of conventional techniques and the so-called rules from all of which I have always liberated myself, though sometimes with trepidation . . .

"I look at it incessantly and (I admit) I admire it. The more I study it, the more I realize its enormous mathematical faults, which I will not correct at any price. The painting will stay as it is as a sketch, if you wish.

"But there is also this question which perplexes me: Where does the execution of a painting begin, and where does it end? At the very moment when the most intense emotions fuse in the depths of one's being, at the moment when they burst forth and issue like lava from a volcano, is there not something like the blossoming of the suddenly created work, a brutal work, if you wish, yet great, and superhuman in appearance? The cold calculations of reason have not presided at this birth; who knows when, in the depths of the artist's soul the work was begun unconsciously perhaps?"

After Gauguin recovered, in the spring of 1898, he sent the picture on to Paris, where it was shown at Ambroise Vollard's gallery. There it attracted considerable attention, and the critic Andre Fontainas discussed it at some length, sympathetically, but from a conventional point of view. For him the picture lacked any clear content; "There is nothing," he wrote, "that explains the meaning of the allegory."

In a letter of March, 1899, Gauguin took the trouble to reply at some length, writing in what was for him a very friendly tone, to explain his method and intention. After mentioning the "musical" role that color plays in his pictures (and will play increasingly in modern painting a prophetic statement), and its power of evoking "what is the most general, and by the same token the most vague in nature its interior force," he continues:

My dream is intangible, it implies no allegory; as Mailarme said, 'It is a musical poem and needs no libretto.' Consequently the essence of a work, unsubstantial and of a higher order, lies precisely in 'what is not expressed; it is the implicit result of the lines, without color or words; it has no material being.' . . .

The idol in my picture is not there as a literary explanation, but as a statue; is perhaps less of a statue than the animal figures, and is also less animal, since it is one with nature in the dream I dream before my hut. It rules our primitive souls, the imaginary consolation of our suffering, vague and ignorant as we are about the mystery of our origin and our destiny.

All this sings with sadness in my soul and my surroundings, while I paint and dream at the same time with no tangible allegory within my reach owing perhaps to the lack of literary education.

Awakening with my work finished, I say to myself, Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? A thought which no longer has anything to do with the canvas, expressed in words quite apart on the wall which surrounds it. Not a title, but a signature . . .

I have tried to put my dream into a suggestive setting and to interpret it without recourse to literary means and with all the simplicity the medium allows: a difficult task. Criticize me if you wish for having failed, but not for having tried . . ."

Today, Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Wher Are We Going is considered as the most iconic post impressionism masterpiece, along with the famous The Starry Night painting by Van Gogh.