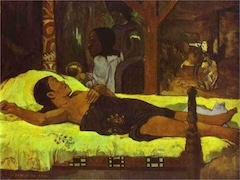

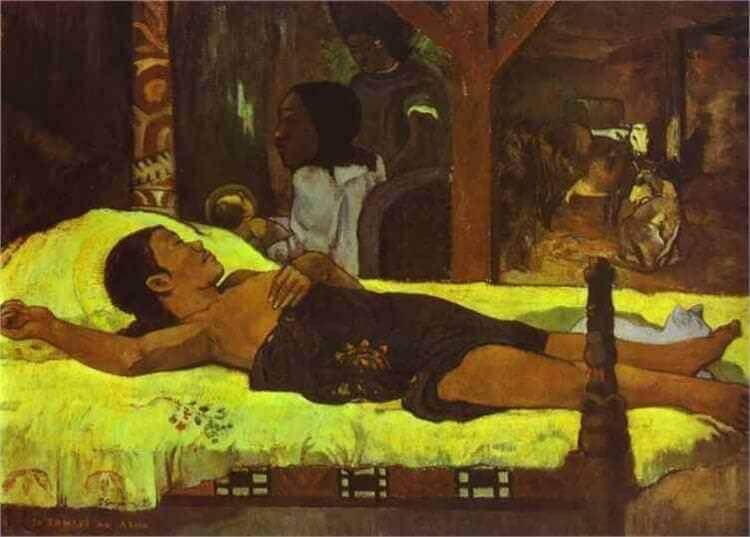

Nativity, 1896 by Paul Gauguin

In July, 1896, 10 months after his second arrival in Tahiti, Gauguin wrote to Daniel de Monfreid:

I am not unreasonable, I live on 100 francs a month, I and my vahine, a young girl thirteen and a half years old. You see that it is not much; it provides me with tobacco and soap and a dress for the little one. If you could see my setup! A thatched house with a studio window, two trunks of cocoanut trees carved in the form of native gods, flowering bushes, a shed for my cart, and a horse. Yes, I have spent money on a house so as no longer to have to pay rent, and to be sure to have a roof over my head . . ."

And in November he wrote that he was about to become a father.

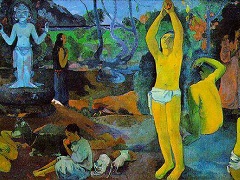

The clarity of the Egyptian technique, its rhythmic alternation of bodily contour and intervening space, its unifying harmony of proportion which allowed him both the "mystery" of which he was so fond, and a grace without softness, all these appealed to the painter's sense of style.

Here then was the setting for this Nativity scene, whose religious allusion is barely suggested by the pale yellow and green halos of the mother and child and the animals behind. It is very different from that other biblical picture of five years earlier, la Orana Maria: that is a traditional subject with native actors, as if to widen a Western parochialism; here a native scene, sacred less because of any specific iconographic connotation than for what it is in itself, an event at once personal and universal. The light around the whole figure contrasts with the mysterious gloom beyond (and the carved trees and native gods of Gauguin's letter); its warm glow, rather than the circles around the heads, is the true halo of the painting, suggestion replacing description. The relaxed hands of the mother, the heads of the infant and the women beyond show a tenderness Gauguin often hid.