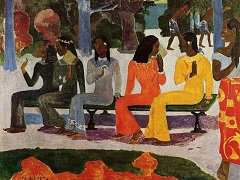

Still Life with Mangoes, 1893 by Paul Gauguin

In Tahiti, when Gauguin painted Still Life with Mongos such as this one, it was as a relaxation from the effort of composing his larger pictures. "When I am tired of doing figures (my predilection) I begin a still life that I finish without a model," he wrote in 1900 to Emmanuel Bibesco. For despite the fact that even when he painted fruit and flowers Gauguin did not feel himself bound by the appearance of nature (its "accidents," as earlier esthetic theory might have put it), the effort of imagination was nevertheless a different one. In such simpler subjects he could concentrate on the "musical" side of his art, unconcerned with the problems of how such abstract constructions would reflect the character and meaning of the subject.

Here he has returned for once to a Cezanne solidity, modeling the fruit in color planes, establishing intervals of spatial recession on the table, building up a close harmony of hue that gives weight and concentration to the close-knit grouping. As in Cezanne, the back edge of the table to left and right does not connect in a single line, because more recession was needed on the right, and the structure of the fruits resembles his. But it is instructive to note - especially in view of the two men's contrasting public personalities - that where Cezanne's clear hues and tones so often produce a clarity that translates itself into feelings of confidence and even gaiety, Gauguin's darker, less contrasting harmonies seem to embody a more somber and subjective mood.